Hillbilly Highway 4 2018 is already in the works . On the way up Friday we took the backroads and make a stop at Pressmen's Home in The Great State Of Tennessee. Pressmen's Home was a community and the headquarters for the International Printing Pressmen and Assistants Union of North America from 1911–1967. The facilities provided on the union's campus, in Hawkins County, Tennessee near Rogersville, included a trade school, a sanitarium, a retirement home, a hotel, a post office, a chapel, a hydroelectric power production plant, and other facilities designed to make it a self-sufficient community.

It is listed on the National Register of Historic Places as a historic district.

Pressmen's Home was the brain-child of George L. Berry, who grew up near the site in Hawkins County, Tennessee. After he became president of the Pressmen's Union, he convinced union leaders to purchase the Hale Springs Resort, a mineral springs retreat. The buildings from the resort formed the core of Pressmen's Home around which later facilities were constructed.

As the union grew, so did Pressmen's Home, adding larger and more elaborate facilities. In its heyday, Pressmen's Home was a self-sufficient town that even provided its own electricity (several years before the Tennessee Valley Authority did the same for the rest of Hawkins County).

Beginning in the mid-1960s pressure from competing unions to lobby the U.S. federal government was beginning to convince leaders of the union that their location in rural East Tennessee was becoming detrimental to the interests of the Union. The Union announced it was moving its headquarters in 1967; lack of funding and merger with other printing unions led to the closure of Pressmen's Home as a retirement facility for union members in 1969.

Since the Union left, several schemes have been proposed to revive the site, including tourist resort, retirement community, and even a state penitentiary. Today the only active project is a golf course and country club that sometimes operates a restaurant. Buildings on the property have fallen into disrepair; several have burned down due to fires that started by accident or by arson

We made our way to Pikeville and the meet and greet got underway . Several of us was sitting around the out door tables when the mountain across the road let go blocking two of the four lanes . Pretty cool and no one was hurt .

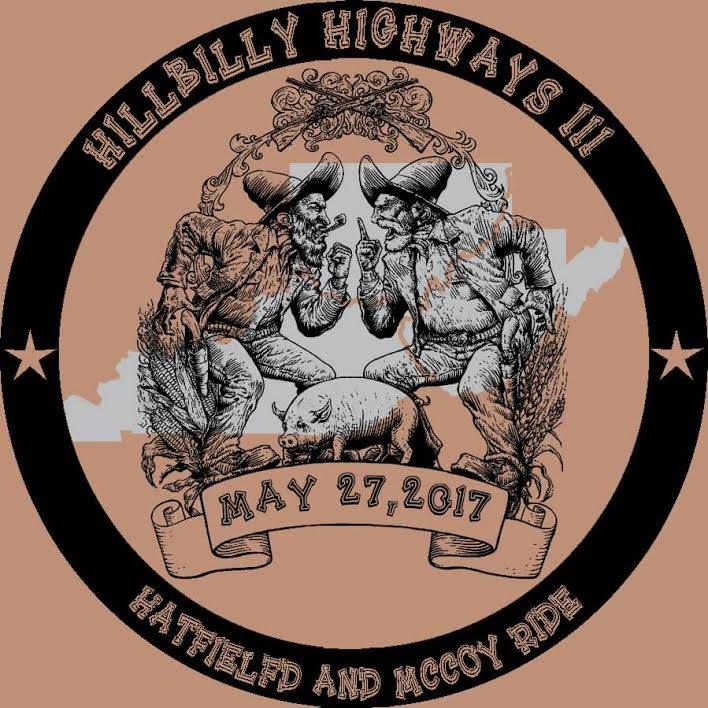

The ride shirts had a misprint not sure everyone that ordered one took it . I bought mine and saw several folks with them on during the ride.

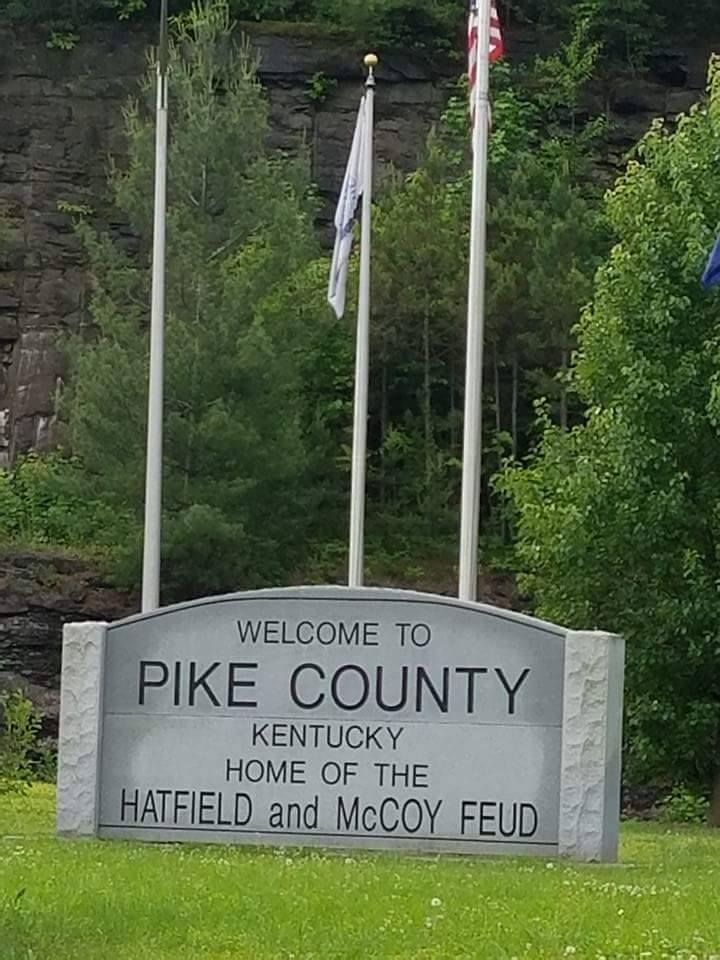

The Hatfield–McCoy feud, or the McCoy-Hatfield feud or the Hatfield–McCoy war as some papers at the time called it, involved two rural families of the West Virginia–Kentucky area along the Tug Fork of the Big Sandy River in the years 1863–1891. The Hatfields of West Virginia were led by William Anderson "Devil Anse" Hatfield while the McCoys of Kentucky were under the leadership of Randolph "Ole Ran'l" McCoy. Those involved in the feud were descended from Ephraim Hatfield (born c. 1765) and William McCoy (born c. 1750). The feud has entered the American folklore lexicon as a metonym for any bitterly feuding rival parties. More than a century later, the feud has become synonymous with the perils of family honor, justice, and revenge.

William McCoy, the patriarch of the McCoys, was born in Ireland around 1750 and many of his ancestors hailed from Scotland. The family, led by grandson Randolph McCoy, lived mostly on the Kentucky side of Tug Fork (a tributary of the Big Sandy River). The Hatfields, led by William Anderson "Devil Anse" Hatfield, son of Ephraim and Nancy (Vance) Hatfield, lived mostly on the West Virginia side. The majority of the Hatfields, although living in Mingo County (then part of Logan County), West Virginia, fought on the Confederate side in the American Civil War; most McCoys, living in Pike County, Kentucky, also fought for the Confederacy with the exception of Asa Harmon McCoy, who fought for the Union. The first real violence in the feud was the death of Asa Harmon McCoy as he returned from the war, murdered by a group of Confederate Home Guards called the Logan Wildcats. Devil Anse Hatfield was a suspect at first, but was later confirmed to have been sick at home at the time of the murder. It was widely believed that his uncle, Jim Vance, a member of the Wildcats, committed the murder.

[/URL

[/URL

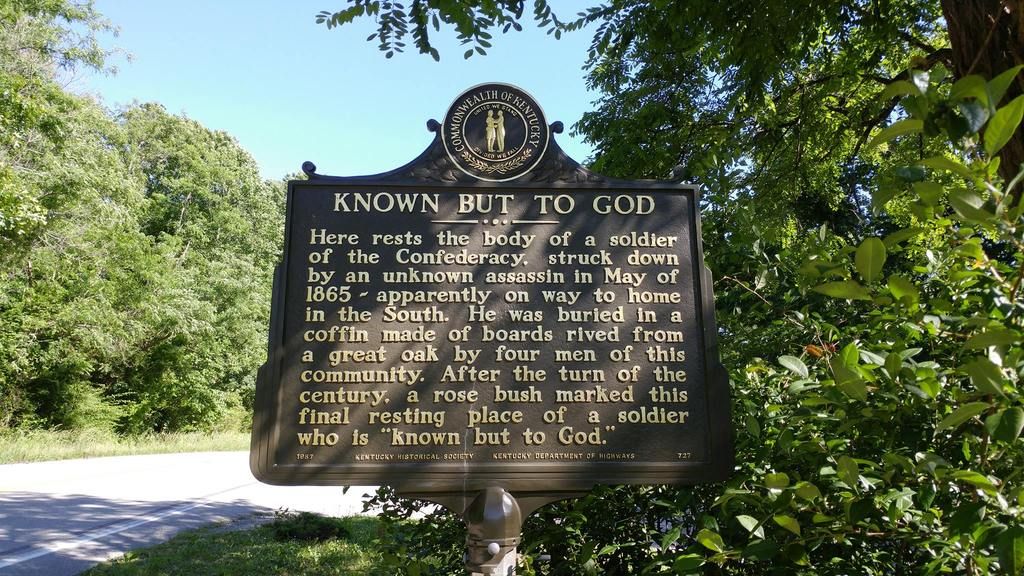

( Updated Thanks to JimmyT wife Patti ) On KY Rt. 80, near Elkhorn City, in the Breaks Interstate Park, a historical highway sign marks the gravesite of an unknown Confederate soldier who is "Known But To God." In May of 1865, the soldier, who was on his way home after the close of the Civil War, was struck down by unknown assailants and killed. Four men of the community, namely Henry and George Potter, Zeke Counts and Lazarus Hunt, fashioned a coffin for the soldier, made of boards rived from a great oak in which he was buried at the spot where he had died. The Potter family kept the soldier's cap and watch in hopes to be able to give them to family members in search of their loved one. Sadly, nobody ever came to look for him. Years after, the keepsakes were lost in a fire. In 1900, a rose bush was planted at the gravesite by Harve Potter and in more recent years a historical highway marker was placed in order to keep the memory of this unknown soldier alive.

Sadly,147 years later, another senseless act of violence was committed at this very site. On Saturday, November 3, 2012, unknown persons destroyed the historical marker. Park rangers had passed the site at 8 a.m. in the morning, with the marker in place. Upon their return at 9 a.m., the damaged site was discovered. Not only was the marker missing, but the four posts surrounding it had been struck down with force. A search by law enforcement later turned up the marker which is damaged beyond repair and can not be reused.

[URL=http://s206.photobucket.com/user/jojovols/media/jojovols023/Hillbilly%20Highway%203/18739184_10206871711950392_5306441646467065635_o_zps80j8yno4.jpg.html]

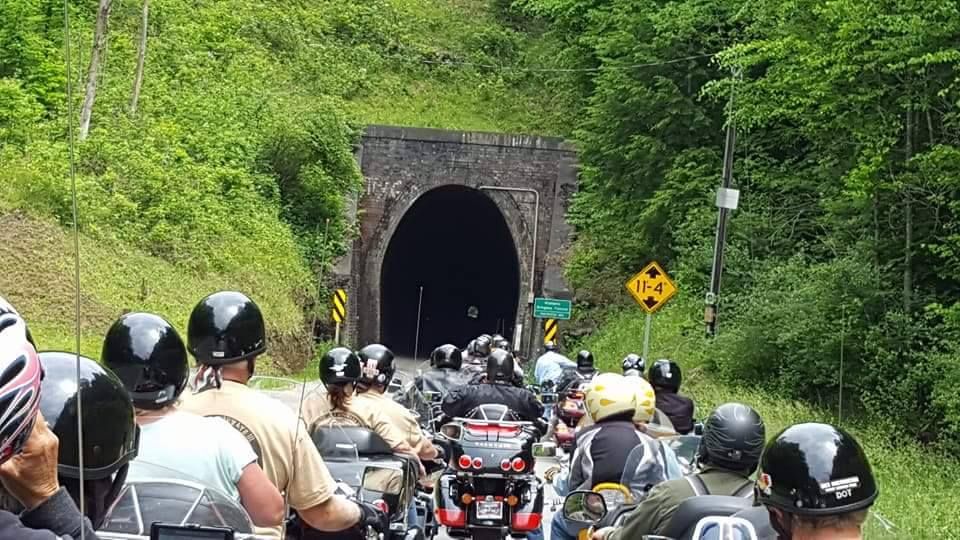

Dingess is an unincorporated community in Mingo County, West Virginia. Dingess is 11 miles north of Delbarton.

Dingess is known throughout the area for a tunnel on a county road south of the town. Originally built for railroad use, it has been opened to one lane vehicular traffic for many years.

The community was named after William Dingess, a pioneer settler.

As of 1894, Dingess contained two hotels, eight boarding houses, four restaurants, four groceries, four saw mills, and a school with two teachers and about 100 students. 133 coal miners lived in Dingess.

The community once garnered a reputation for being a lawless land. In his book They’ll Cut Off Your Project, Huey Perry, wrote “Old-timers there said it was common practice to have a killing once a month. As ‘Uncle’ Jim Marcum described it, ‘Why, a colored person couldn’t think about riding through Dingess. They would stop the train, take him off and shoot him, and nobody would say a word. Why, they would even stop the train and take all its cargo. It was a wild country then, and it ain’t much better now.’”

From 1900 to 1972, approximately seventeen lawmen were shot to death in the area which stretches fifteen miles along Twelve Pole Creek.

IN 1901, robbers raided the community, dynamiting a large safe. According to a November 23, 1901, edition of the Bluefield Daily Telegraph: "Citizens were on the scene almost immediately after the heavy report, and the burglars hadn’t time to gather up their booty as a number of citizens opened fire and probably forty shots were exchanged. The burglars, who secured a lot of valuable jewelry, escaped on a hand car which was recovered later four miles from Dingess, and on which blood spots were plainly visible.

Outstanding ride with great weather I just knew our ass was going to get wet on the way home Sunday however we never had a drop hit us . Hillbilly Highway 4 2018 is already a GO for next year . Thanks Reb for getting us all together again